Release process

Update: See https://chromium.googlesource.com/chromium/src/+/HEAD/docs/process/release_cycle.md#Overview for more information.

OPINION EXPRESSED IN THIS DOCUMENT ARE THE VIEW OF MARC-ANTOINE RUEL AND ARE NOT REPRESENTATIVE OF THE VIEW OF HIS EMPLOYER, GOOGLE INC. </blink>

Google Chrome Infrastructure

Upgrading 200 million users within 6 hours

Initially presented at agilis.is conference in Reykjavik, Iceland on 2011-11-14 by Marc-Antoine Ruel. This document is a flattened version of the presentation done there.

As a team, we provide the infrastructure necessary to enable the current release process, which I'll describe during the presentation.

Web vs Client app

Web app?  Client app?

Client app?

You cannot approach client project infrastructure the same way you do for web services. The deployment cost is largely different. The feedback loop, to know what's happening on the user's machine, has much higher latency.

Most web services and web sites use really fast release cycles. I've heard some big site having a 6 months release cycle but that's not the norm. And I presume if you are here today, you don't want to be on the laggard side. I'm going to focus this presentation on client side which has totally different and interesting challenges. We wanted Google Chrome to feel like the web and not like shrink wrapped software. My talk is focusing on techniques used to enable this vision.

Points of friction

Reduce friction for

- devs

- users

- software

- security fixes

First, you cannot be agile if you have friction along the path. Being agile is all about reducing the friction from the inital requirement, to the updated requirements to the end result, all in an iterative feedback loop. If you don't look at the whole picture, the end-to-end experience breaks down.

To ensure a delightful experience for the user, we need to react fast. I'll focus on four points in this presentation with how we addressed each of these friction points.

Friction for devs

« All I want is to git push »

Let's start with friction for developers. That what most people thinks about for agile development, staying up to date with the requirement from your client and updating accordingly. But in practice that's not sufficient. There's mentality and practice changes to ensure that the lean small team agility scales to hundreds of developers.

Feature branches

Big no! no!

Feature branches are the worst of all evils. Let me explain. Most of the time, the feature doesn't work well on the branch, but everytime, it doesn't work at all when merged back on the master branch. Even more, they are disruptive to merge and most of all; they always need to be merged yesterday.

The incentives are just plain wrong. First, it's too easy to underestimate the cost of the feature branch for a product manager. The developer wants a stable code base to work on. But staying on old code means that he doesn't see any refactoring going on, so when he merges back, he may need to redo his change completely on the new code. What this means is that after a while, nobody evey dare to refactor the code in fear of retaliation.

Working on master

Let's all work together

Most of our features are developed directly on the master branch and disabled just after forking a release branch if not stable worthy. Let me do a pause here, we have 4 release channels in increasing order of freshness, stable, beta, developer and canary. The canary strives to be a daily build. That's why the canary is very unstable as all the experimental features are enabled, once a developer release branch is made, all the experimental features that have no chance to go to stable in their current state are disabled on the branch. They'll have their chance in 6 weeks as we do new major release every 6 weeks. Devs like to work on a branch that works for them so they can do a fast code/build/debug cycle. If unrelated breaking change breaks their local checkout, they will be staled. Scaling up the number of developers means scaling up the number of commits per hour.

Code review

You thought you knew how to code?

First line of defense is code reviews. We require it for almost all of the commits going in. There are exceptions but in general, not doing code reviews is frowned upon. Code reviews are a great tool to improve the code quality before it gets checked in, and has the side effect of helping new contributors to ramp up much faster by getting immediate feedback for their first change. Having effective code reviews require the developers to care about giving thoughtful feedback. That's a culture that is hard to enforce after starting a project.

Question: Who does systematic code reviews on their projects?

Continuous integration

The second line of defense is continuous integration.

Question: Who uses continuous integration in their projects?

To work on master branch, the code must work. It's all about making sure each and every single commit is valid enough so that all the main functionality of the project is kept. Let me precise a little bit here. We don't want to product to be completely perfect; good enough will suffice. Good enough that we can actually release a build directly from it. That's a huge mentality ship for certain developers but that's a requirement. This also requires a huge investment in the infrastructure. In practice, we use buildbot, which is a open source python framework to manage a centralized build system. It's also used by WebKit and Mozilla and others. In practice, the tool doesn't matter, the process matters. We try to keep the testing cycle as low as possible to reduce the latency so the feedback loop from commit to test results is as tight as possible. To help with reducing tree breakage in the first place, we also use pre commit tests.

Keep master from exploding

What is your legacy?

A colleague wrote recently; we often discuss our software engineering practices, especially code review and testing, but I think that sometimes the reasons for our practices get lost in the mix. We aim:

- to keep trunk shippable; and

- to have enough automated testing to continually prove that trunk is shippable.

This is in support of our goal to release as often as possible, which makes us more agile. We absorb the extra costs of thorough code reviews and testing since we believe that these things help keep us agile and reduce costs in the long run. Code reviews and automated fuzzing also reduce security risks.

These goals and practices are really suited to the age of the Internet, where software deployment is fast and easy. Compare that to a few years ago where people where still getting their software on DVDs!

Question: Who installed software on DVD/CD this year?

It's especially true for server-side only projects but it is now also true for projects with fast auto-updates à la Google Chrome.

Pipelining releases

I briefly talked about our release process but I want to take a pause to explain it more in depth.

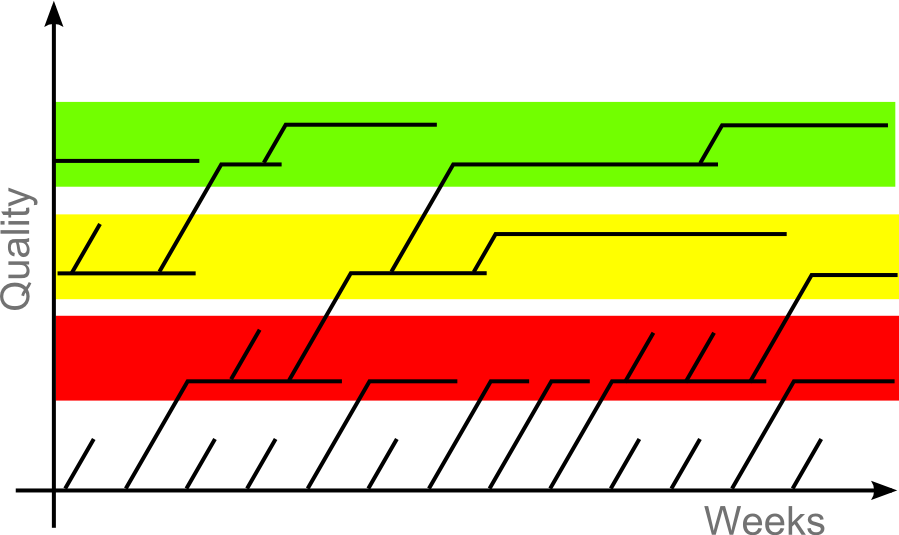

This busy graphic represents our release process. Each line is a branch in our source tree. Horizontal lines are what is released to our users. An aborted branch is one that didn't pass QA. The red section is the developer channel, the yellow section is the beta channel and the green section is the stable release.

We also have what we call the canary channel but I'm not depicting it here because it's a release done directly from trunk. This is to prove that trunk is always stable enough to make a release out of it. The canary channel strives to be daily or at least every few days. The developer channel is roughly weekly. We then release one major beta channel and stable channel release every 6 weeks. A dot release can be done on the beta channel or stable channel to introduce more fixes, which is depicted here as branch inside the same channel.

Indeed, we have very good people that manages these branches. The trick to make it workable is to send our dev channel release in the field, look for bugs found out and merge fixes back in the beta or stable channel as needed. Also, and let me put emphasis here, every code change is done on the trunk first and then merged back to a branch. No change is ever directly done on a branch.

We try to have our branches as short lived as possible. With a 6 weeks of dev, beta and stable channels, a branch lives roughly for 18 weeks, or 3 months. Which means that we don't care about any code that is more than 3 months old, which helps us tremendously to stay flexible on the code base refactoring. That's really a huge advantage. The pipelining here is really what makes us much more efficient because we get different kind of feedback from each of the channels. Let's talk about user feedback.

Friction for users

Users don't like questions and second, they don't like to be interrupted. Many of them don't want to do the the cognitive effort of task switching when it's not their will. Every single dialog box is a context switch. So we strive to only ask meaningful questions. For example, that's the main reason we are not installing in the Program Files directory, it's just too much friction for the user. Delight the user and make the application as easy to use as a web page.

FYI, UAC prompt is the dialog box with all the remaining of the screen being grayed out, specific to Windows.

Update on restart

Please! Do not prompt on start!

As an example, I was away from my main workstation for a week and upon reboot, one piece of software and one device driver nagged me to be updated. After 10 minutes, too many clicks and 90 megs of download, I finally could resume working. And as an OS, don't tell me you have 8 new important updates to install. You are the OS, you should have One update to install at any given time, and One and only one per supported applications.

Thanks for wasting my precious time, folks. So please don't make your users angry at you. Nobody likes a dialog box poping during a web based presentation.

The reason I'm raising this point is that it's important to reduce the number of different state each client can be. As you increase the number of one-off patches, having users to upgrade multiple modules independently, you increase the odds of something going bad. So it's easier, at least for us, to make sure everyone gets the same bits and disable functionality as needed.

Question: As an example, who used Google Talk video chat or Google+ Hangout? Who recalls installing the plugin to make that work? Who recalls updating the plugin? Well, it probably updated since you installed it, you just never realized and you probably don't care.

Frequent releases

Gradual, gentle changes

By releasing more frequently, the number of changes per upgrade is reduced. This means that users will see smaller changes more frequently, instead of big changes every year or so. This makes it easier for users on the long run, as you don't need to do big training for non-tech-savvy users. Also, users become used to see gradual changes occuring, which reduces the natural change aversion some users may tend to have.

User feedback channels

What if you do an error? Getting good feedback from your users is not a simple task. They may not know what they want. They may not understand what is happening. « Google stopped working ». Maybe the user means he got power outage. So getting usage statistics is gold. In our case, we chose for an opt-in. So the user has to check a box to have Google Chrome send usage statistics and crash reports.

Also, decoupling the automatic update software from the client software helps recovering in case of failure. I recommend to keep them as separate as possible from a software version standpoint. Especially when the failure comes from third party software; In our case, we use Omaha, which we open sourced. I'll leave a reference at the end of the presentation.

Testing in the field

Continuously hacking your users *

* yes, you are a guinea pig

One interesting thing once a project grows large enough is to be able to do controlled A/B testing with a small percentage of your users. To be able to do this, all the infrastructure must be set to be able to disable the experiment really fast if something goes bad. Also, the intrinsic goal of the testing is to gather feedback so we must make sure we are getting it. On a web service, it's relatively easy to manage. It's much more fun to do on client applications. We made privacy aware anonymous feedback infrastructure to gather experiment information only from users who opted to send statistics.

This gives valuable information for things where the test matrix is too large. Here are a few examples: test OpenGL implementation robustness, test effectiveness of different on disk web cache heuristics, implement new SSL designs and verify its compatibility in the field, tweak omnibox or autofill heuristics, network packet retries heuristics, etc. Lots of things where it's really about tweaking the best values or the best automatic selection of values. The important thing here is to correctly do the measurement and do it both anonymously and in an non-intrusive way.

Friction for software

In that case, I'm specifically referring to third party software. There's the third party software extending the browser, like plugins and extensions, but the actual web pages are also to be considered third party software, since it's code interpreted inside the browser. Each new version of the browser may affect the way the plugins, extensions or web pages are handled.

Don't break the web

Not Everyone Uses

body {

text-transform: capitalize

}

But We Still Support It *

* Marketers Really Need It

Similarly to how Microsoft trumped compatibility with older applications in each of their Windows OS releases, web browsers strive to not break the web. And that's true for every web browser. The testing matrix is much larger than what we can actually test, so it's more efficient for us to ship the developer channel often and early, and if we break things people care about, we'll get feedback about it soon enough. Indeed everytime a regression is detected in javascript, css, html parsing, or that we found a new http proxy misbehaving in an interesting new way, a regression test is added. But be realistic here, that is still not enough because the gap between the spec, like the HTTP spec, and third party programmers expectations is too large.

Don't break extensions

In addition, we don't want to break the 62 users of this extension. Simple things need to stay simple. In that case, it may mean either versioning the API and eventually dropping the older API versions or being backward compatible all the way up to the initial version or being just very relax in the bindings and hoping for the best.

Actually, we solve the problem since we make the update ping infrastructure Google Chrome uses for itself available for extensions too. This is a huge benefit for extension developers because it's like having all your users running tip of tree all the time, also on the latest version of the browser, with only a worst-case propagation delay of 5 hours. All this is free for extension writers. This is a huge difference from the experience on other web browsers. And extensions are updated as you are using the web browser, without ever requiring the user to reopen his windows to be updated. This is a huge benefit for the users since I found out upgrading extensions can be very annoying in some case for some applications.

Show respect

It's harder than it appears

Unless your process is running on dedicated hardware like a gaming console, you need to try to show respect to the other processes so the OS doesn't misbehave. Here's an example of things we do. Bombing the system with a number of utility processes. Using too much physical memory. Using too much bandwidth for automatic upgrades.

One workaround is to use incremental upgrades so we only download the delta. Another is to limit the number of processes and further more by the amount of physical memory. The processes use shared memory as much as they can and trim the in-cache memory aggressively. We slow down background tabs to reduce CPU usage, to increase battery life. We slow down the various timers while on battery, also to increase battery life. But still, what if you are breaking hooks from an anti-virus software or even worst, from malware hooking on kernel32, which brings me to...

Don't expect to be respected

What do you do with malware crashing your app?

Who's fault is it?

One recent issue was what do you do if some security software thinks you are a virus and tries to delete your application? This may mean pushing new code that will work around the problem. That's what we did, within half a day of learning about it so many users may even realized. To achieve this, your release team must always be ready to fire and manual QA must be minimal. I'm not trying to point fingers here, that's the kind of thing that cannot be tested by all security vendors. We just have to live with that possibility.

But still, what if some malware hooks your process, and crashes because it fails to access the sandboxed process? Which brings me to...

Security

What is security?

... security!

Security can be viewed as making sure that no action is done on a user's behalf by a third party that could go against his will. If you have valuable information, people will try to hack you in all possible ways. Spoofing our DNS name, proxies serving fake SSL certificates and on the fly packet translation. We've seen it all. Many of these are hard to address from the web service directly. Having a end-to-end solution helps there, even if it is for a subset of users. You can't just think about security without looking at the overall picture. One important thing we developed is the Google Chrome sandbox. Feel free to meet me after the presentation if you'd like to talk about it.

Always look for the easiest path, that's what crooks do. They are willing to invest a significant amount of time in searching to figure out holes in the security mechanisms. And once they find something, they will use it fast to affect as many people as they can.

How do we address that?

You deploy fast?

Which is preferable?

Average upgrade delay of 1.5h or 3h?

That's simple. Put your bits out as fast as you can. Seriously, our security guys were argumenting about the upgrade ping rate. Is it better to ping at every 3hrs or 5hrs. Doing the check on startup is the worst time you can do that. The system is already CPU and I/O bound. But updating still means for most users to notify the user only if a real immediate risk is present. So the basic idea is to update the system but make it almost transparent and hopefully magical to the user. Subtle enough that most users won't realize but power users will act upon. In both Google Chrome and Chrome OS, we decided to add a little green arrow when an update is ready to be installed.

Enterprise deployment

Who's in charge to decide who's upgraded?

Enterprises like to control deployment of the software used by their workforce. That's normal, a disruption in their workforce could cost a lot of money to the company. How to conciliate that with forced automatic upgrades? First of all, because of our release pipeline, they can canary themselves a few users on the beta channel or the dev channel, which gives them an astronomical 6 to 12 weeks to find out quirks and if it's not enough, they can delay stable update a bit more if really needed.

We created tools for administrators to delay updates or apply policies to installations of Google Chrome or Chrome OS on their domain. What helps us, and them, here is that each upgrade only represents 6 weeks of changes that occured less than 3 months ago, so the freshness is always relatively good. Second, they have one package to control, not sixty billion small component upgrades to mess with. This reduces a lot the overhead of patches management. In the end, everyone wins with a more secure and simple environment.

References

- Chromium and infrastructure

- You are on the right site, feel free to navigate around!

- Omaha (Windows updater)

Note that I forgot to talk about Build Sheriffs, which are an important part of the cultural team mindset that helps making sure the team is make progress in a cohesive way.

Obi-Wan Kenobi is copyright Lucasfilm